Camille Billops

491 Broadway

Camille Billops’ loft in SoHo was a place of artistic experimentation, intellectual exchange, and legacy preservation for her creative community.

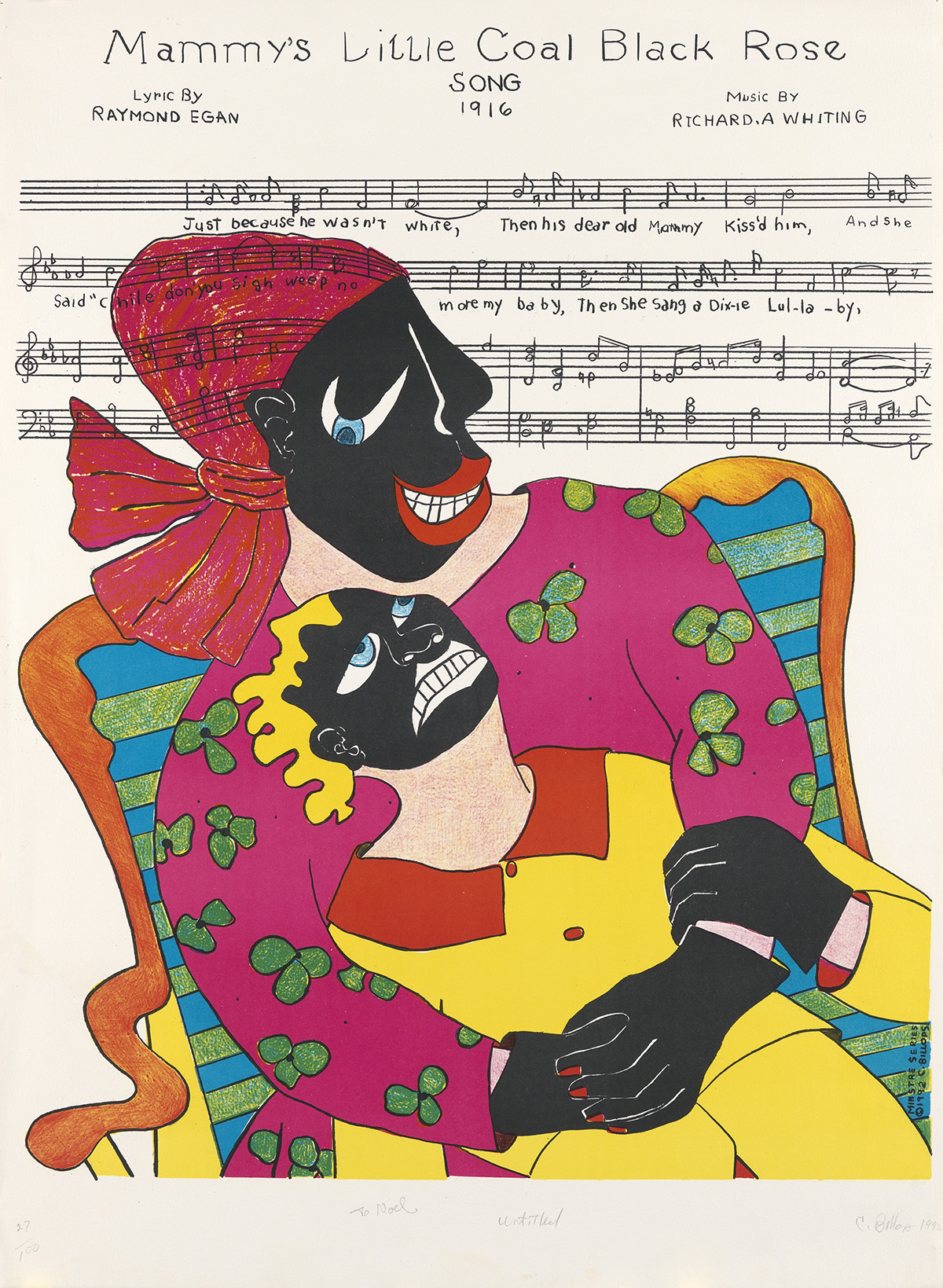

A multidisciplinary artist and filmmaker, Billops began her art practice as a ceramicist at the University of Southern California in the late 1950s. and later moved to New York City in the 1960s to further her artistic career.

As a young woman in the 1960s, Billops moved to New York City to further her artistic career. There, she found herself involved with many Downtown-based art activist groups. Invited by its leader, Benny Andrews, she became a co-director of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) during its advocacy for more recognition for Black people in the arts. Her participation in this group allowed her many exhibition opportunities and led her to purchasing property in SoHo, where many of her contemporaries began to live, work and congregate in the 1970s.